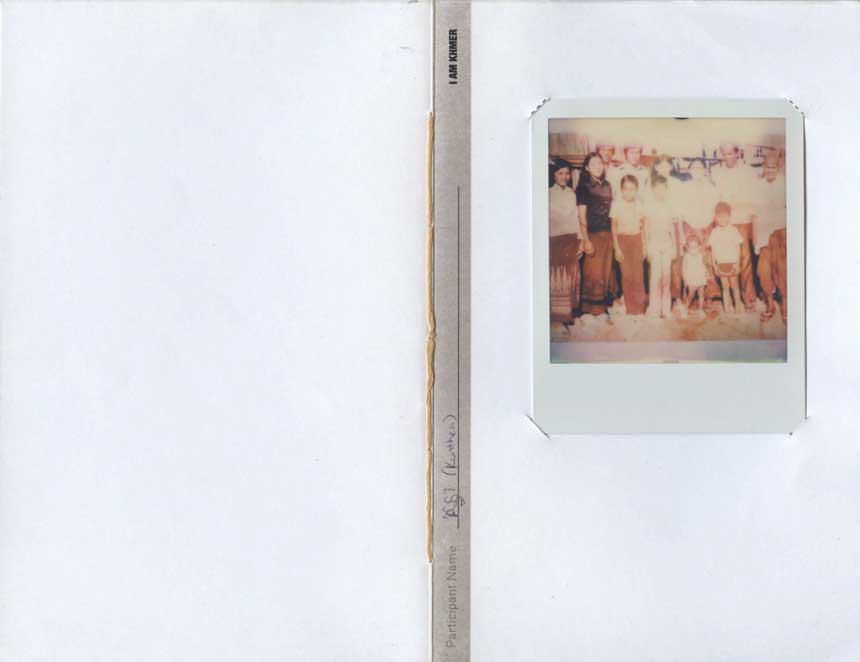

Pete Pin: I Am Khmer

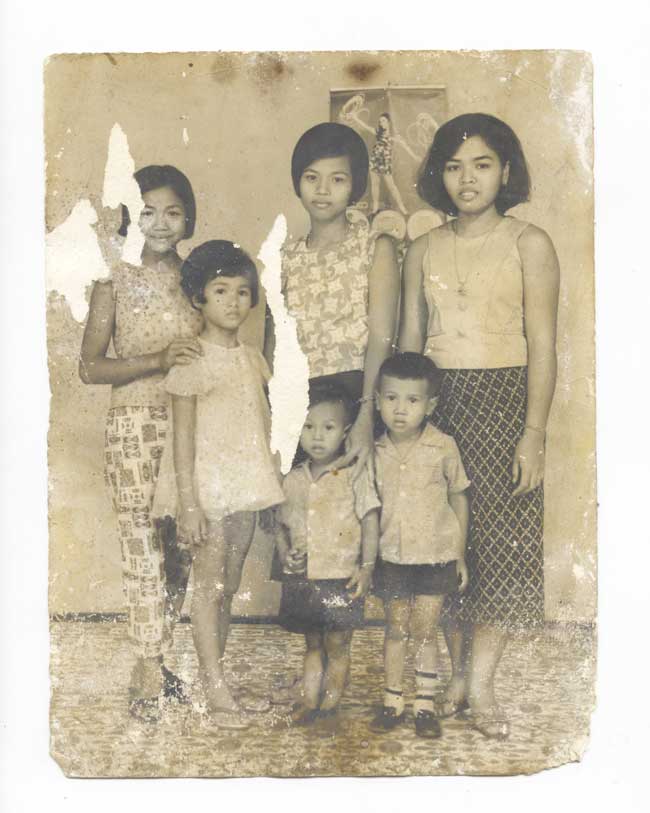

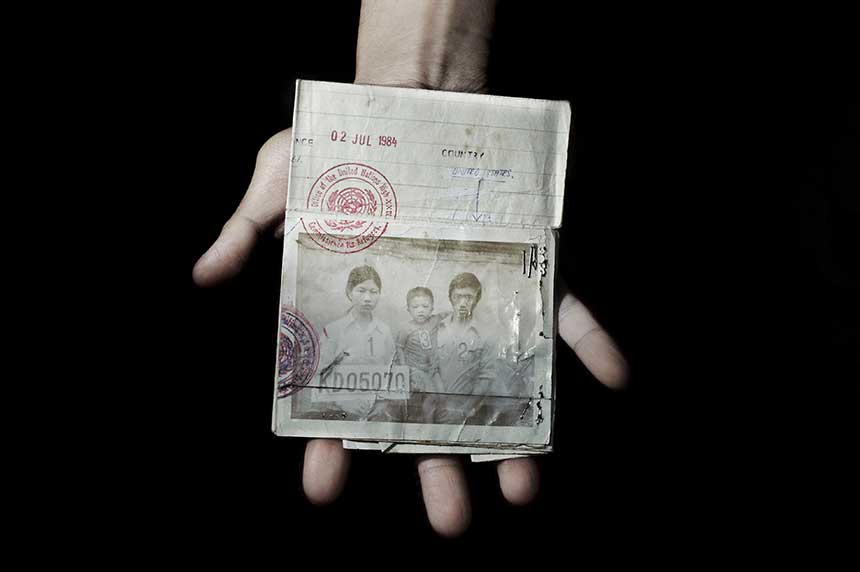

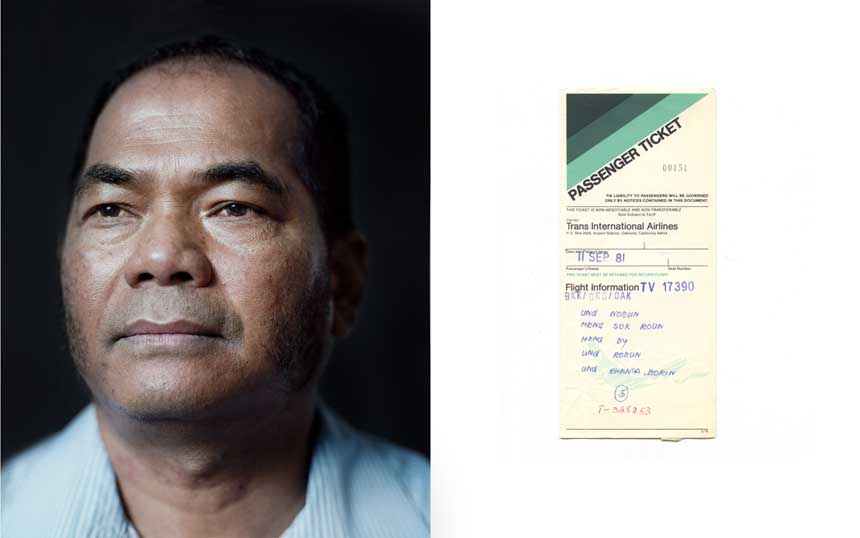

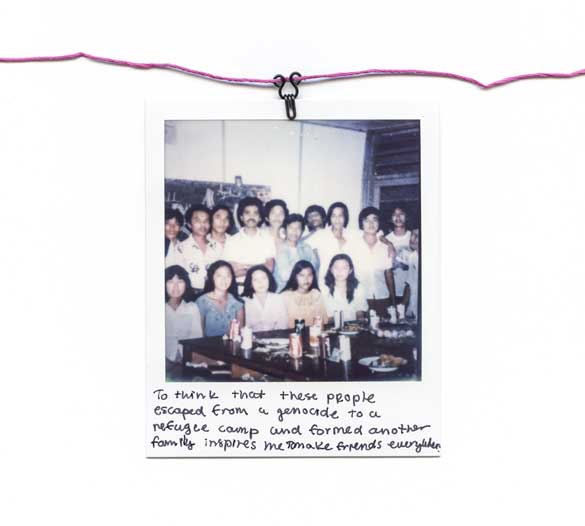

“Over the years I have been invited into countless Cambodian homes to photograph. I have watched mothers and fathers pull out boxes of documents and photographs from the past, have witnessed as they share stories and experiences from the past with their children, often for the first time, as my grandmother had those years ago.” - Pete Pin

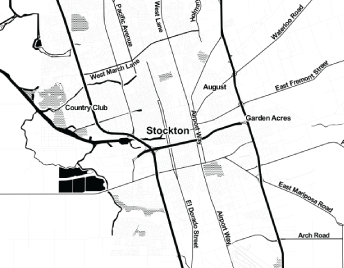

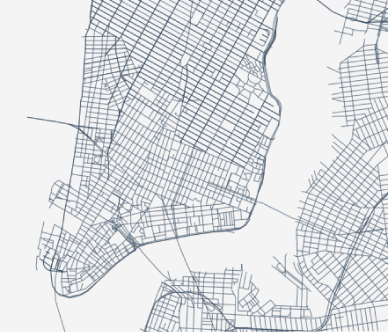

More than three decades after the Killing Fields, the aftermath persists in the Cambodian American community. It is felt in the silence between generations. Cambodians who lived through the genocide not only remain silent because they do not know how to speak of what they lived through, but often because they literally do not speak the same language as their Cambodian American children. I Am Khmer is a participatory, community-based project in development that explores memory and identity in the Cambodian American community.

While it has spanned many years and multiple cities I Am Khmer began with a single conversation between Pin and his grand-mother. Through this powerful family moment, his Grandmother shared a photograph that changed his understanding of his family's history, and shifted the trajectory of his documentary practice.

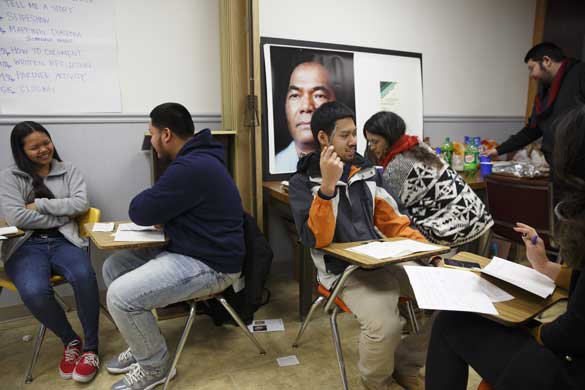

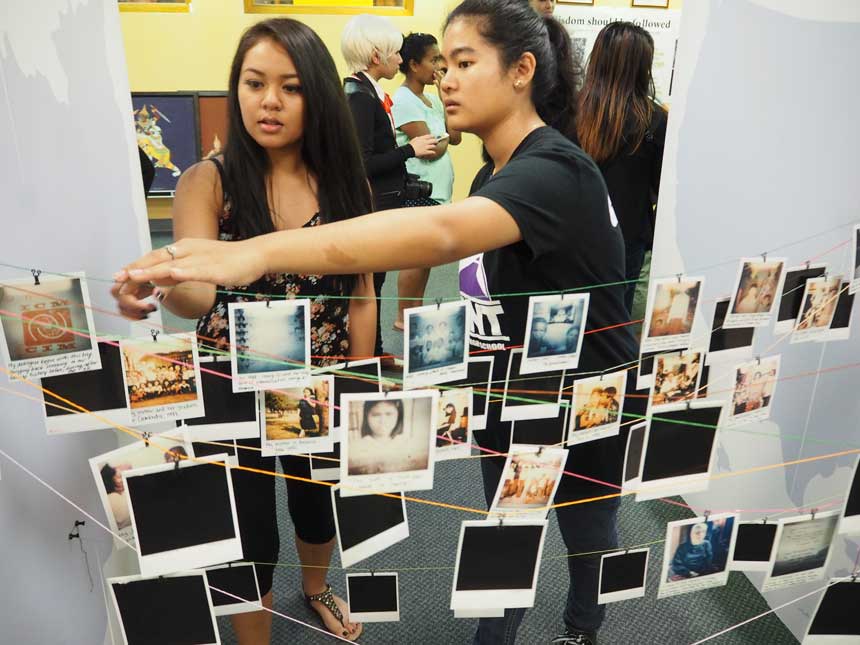

Throughout the project, Pete has sought to not only document a diverse and evolving community, but to use photography as a vehicle for sparking intergenerational dialogue and understanding. While beginning as a traditional documentary project, I Am Khmer has since evolved to feature a national series of collaborative workshops where participants interview family members, document family photos, and work with Pin to tell their family's story.

Over the years Pin has engaged a multitude of tactics and strategies for using photography as a tool for collaboration and community engagement. By revealing the evolution of his process we hope that this document will help others expand their own practice. Follow the timeline below for an abridged history of Pete’s process as he moved from first-person documentary storytelling to participatory practice.